“What should I get my grandfather for Christmas?”

The question seems preposterous, so I keep manipulating the paper, head bent over the irregular present, attempting to find the best fold for the wrapping on my latest task. Why is this young boy asking advice from us, total strangers, within our square booth, in the midst of a busy Toronto mall?

Emily is unphased and responds while deftly cutting a perfect straight line through the toy box design.

“That question is hard to answer because I don’t know your grandfather. What does he like?”

“I don’t really know.”

There is a crowd in front of us, gathering, watching our work. I look up. A young boy, probably twelve or thirteen, a little taller than the rest of the posse, perplexed, honestly enquiring, waiting for some guidance on where to begin the evening’s shopping.

“Well have you thought about something he likes to eat, maybe a box of candies or a package of mixed nuts?”

“Yea, that might work. He would like that. I will get my grandfather a box of candies. Thanks.”

“How do you make the ribbon curly?”

That last question is directed at me, from a different person, as I am adding the finishing touches.

“Wait around for a moment and I will show you.”

I tucked the elongated strand under the previous knot, criss-crossed the two ends and pulled it tight.

“Now you open the scissors, like this, drag from the bottom to quickly scrape the dull side, and voila – curls.”

“Cool. Thanks,” and the boys disperse, disappearing into the flow of a seemingly endless throng of people.

“Where does this one go, Olena?”

She is the one responsible for me being here tonight. Indirectly. Olena has been volunteering at the food bank. This week the work involved a shift at the booth, three days before Christmas, wrapping presents for shoppers, five dollars for a small gift, ten for a large one, all the money a donation for the charity. She needed another person and invited Olga, her mother, my spouse, to help, who in turn recruited me in “supporting our daughter”. Difficult to say no.

“It belongs with the larger one here. Can you work on this bunch next? The guy is going to be back in about fifteen minutes. He doesn’t care what kind of paper, just as long as each one is different.”

A sweat top, with a hoodie, matching sweat pants, and a pair of blue clogs. No boxes. Stores don’t appear to be supplying them and we don’t carry any in our booth, so it requires some creative paper machinations. Again. Clothes have been the most common commodity, primarily those for relaxing. Mittens, hats, housecoats (“I definitely think this one needs to the striped paper.”) Toys r Us has been a popular source. Hot Wheels, back packs, stuffed toys. Rachel, the high school student accumulating volunteer hours is tackling several from two 30ish guys, still in their dusty work clothes, attempting to ensure something will be under the tree. Knock off a few items from the list, quasi-professionally wrapped, contribution to a good cause. Not bad for one evening of work.

“Dad. can you help out this woman? She has been waiting. Mom, can you give Dad a hand?”

Non-stop since 3:00 pm, there is finally an opportunity to sit down at 6;30, a lull, some calm before the next onslaught of creams, watches, Metallica t-shirts, and more sweat tops. Many young men scrambling, woman managing packages and children, Mary who wants to take a picture of the decorated package before sending to her son (“I did this by myself for years…. try taping the corner before folding. Yes. Perfect.”); a kaleidoscope of people and backgrounds, hoping their selection will bring a smile to a parent, a child, a girlfriend, a grandfather, wanting to share their thoughts, this moment, this season of giving.

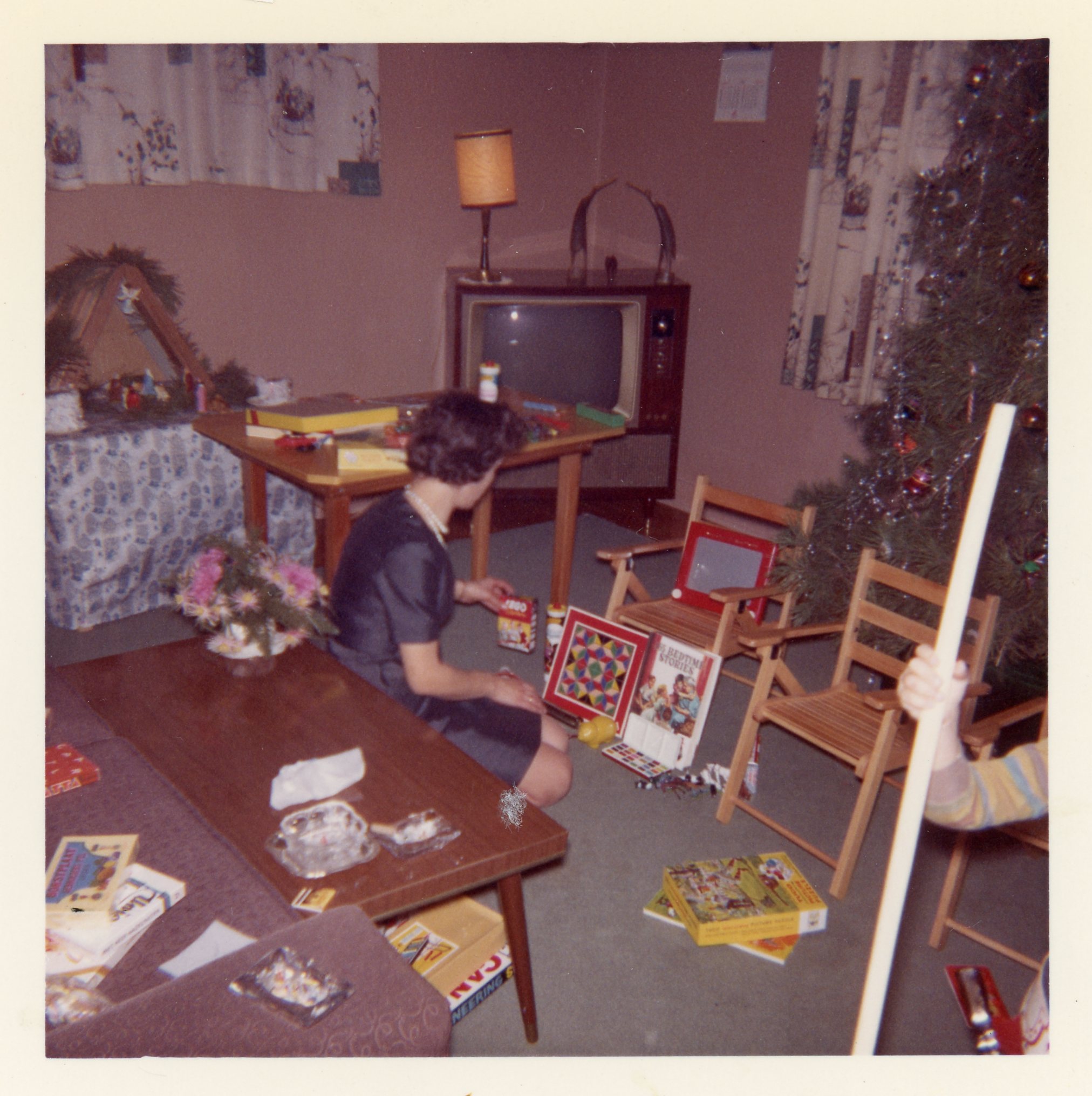

Christmas is my favourite time of the year.

Then suddenly we laughed and laughed

Caught on to what was happening

That Christmas magic’s brought this tale

To a very happy ending.

Merry Christmas, Merry Christmas,

Couldn’t miss this one this year.