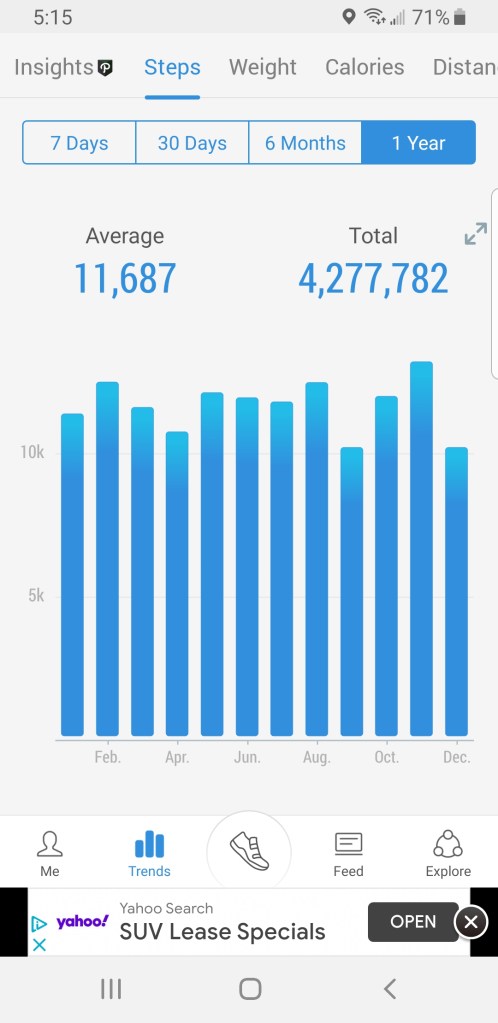

When 2020 started, I made a commitment to walk an average of 10,000 steps per day.

I deliberately used the word average knowing there would be numerous days when I would not meet that target but would compensate on other occasions with a larger number of steps. My goal was publicly announced in front of a room full of professors at a new faculty orientation in the first week of January back when I was gainfully employed and everyone was going into work, in person. Remember those days?

While working, I was able to manage four to six thousand steps in a day through regular activity up and down the stairs at home, walking in from the parking lot to my office, attending meetings at multiple locations on the campus or visiting a colleague’s department. The remaining steps could easily be attained with a short walk around the neighbourhood after dinner. I found creative ways to hit the target even on days when sitting was the default position, such as walking loops around the airport waiting to board the plane or following a continuous path through the living room and kitchen in the house on stormy evenings, reversing the direction to get a different view.

The COVID shutdown meant work was completed exclusively in front of a computer screen for every interaction. Attending meetings was the click of a button and the only exercise was a trip to the bathroom to expel the increased number of coffees consumed or to pop downstairs for some lunch. Reaching my step target would mean, therefore, more deliberate attention to time and distance. I would eye the day’s calendar, determine where there would be a half hour window where I could walk the block with the knowledge the route would be about 20 minutes and accumulate 2,000 steps. I began to think only in step counts: back and forth to the drug store was 2,700 steps; the street circling the community was 5,200, a jaunt to the grocery store was 6,200. When I retired from work at the end of June the challenge was to discover longer walks for a change in scenery and to avoid a Groundhog Day scenario each time I ventured out the door.

One of the preferred paths took me through the local park, around the small ski hill, and back home along a paved trail beside the creek where I strolled past a fledgling display of encouragement assembling at the base of a tree.

The effort appeared very quaint. The square sign summed up the effort best: “Sharing joy through painted rocks. See a rock, paint a rock & bring a rock. Join our rock garden use our hashtag, #EtobicokeRocks”. I thought the idea to be sweet, a creative effort to keep people optimistic as we endured the restrictions of COVID. Walking was one of the only safe methods to maintain some exercise and this display provided encouragement, an appeal to all who pass to share in support of each other. The effort made me smile.

The idea appeared to catch on. Some garbage around the tree was cleaned up, more painted rocks were added, people were paying attention. Some smart aleck deposited an empty beer can amongst the rocks. It was gone a few days later as the more thoughtful additions were piling up.

The rock garden had grown with colourful and clever additions. The messages were for hope and happiness and fun, in an assortment of shapes (the square rubics cube) and sizes, some from children and a number from adults. The greenery of the tree contributed to an aesthetic of enjoyment for all passersby. I couldn’t help but stop to pause and scour the ground for new additions, read the words of wisdom, reflect on the message, and contemplate on what my contribution would be.

As the fall rolled around the number of COVID infections increased again, restrictions came back, and the fatigue of a prolonged pandemic settled into the psyche. The end appeared further away and new painted rocks were scarce. At the end of November we received our first snowfall, covering the collective effort to spread cheer and joy. Renewed lockdowns only added to the darker and gloomier days leading into the new year.

But rocks don’t melt. They are undaunted by foul weather. They remain firm and steadfast. The messages of joy and hope displayed in this grassroots monument to collective healing, however battered, persist to form the foundation for a spring, to help us endure and knowing all this too shall pass. It is the continued acts of kindness and consideration and every effort, small or large, to find ways to smile or laugh which keep our eyes on the horizon for the day when we will all get back together, again.

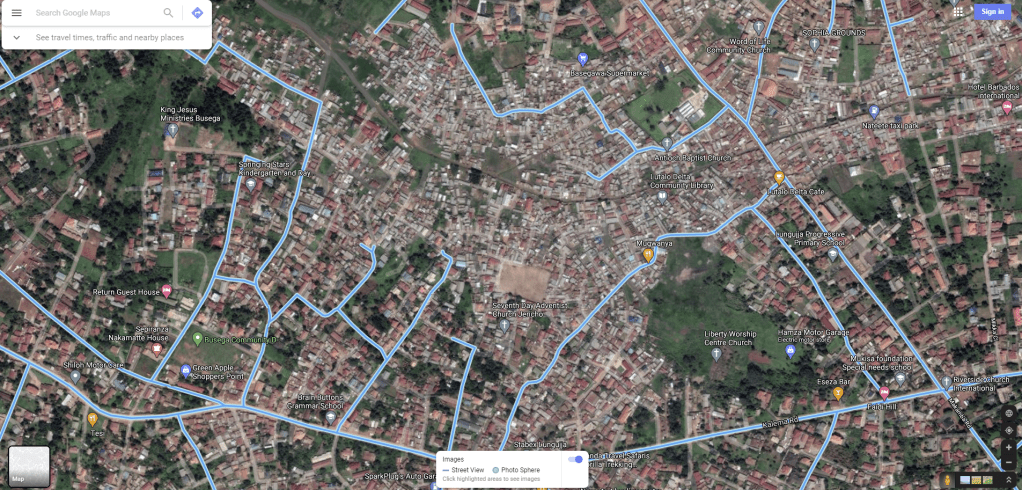

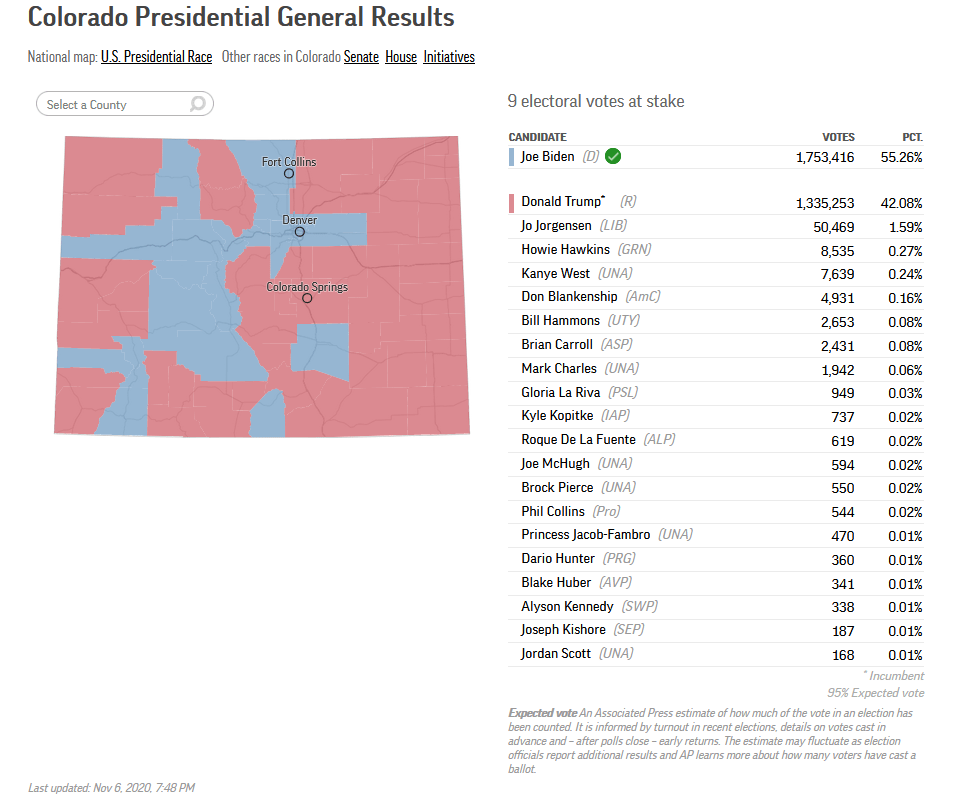

I completed my goal despite challenges in December to end the year with an average daily step count of 11,687. To answer the skeptics call of “pics or it didn’t happen”, I am including a screen shot from December 31st of the Pacer app on my phone which documented every leg movement in 2020. My new challenge will be to replace the time I spent walking with other forms of exercise. The discipline necessary to achieve this objective will prove more difficult than finding the time for walking but I will remember and recall the messages of the painted rocks with their words of encouragement and hope to overcome and “bee happy”.

So for those who work in our hospitals and in our nursing homes, for those who abide by the protocols, for those who still greet you with a smile and a good morning as you pass them six feet apart, for those who share stories across driveways or balconies or computers, for those who paint the rocks, we salute you.