When the children were young, our family enjoyed playing a board game entitled, The Tortoise, the Fox, and the Hare. The premise was simple: a race to the finish line, first one crossing wins. There was a pair of six sided dice for each contestant except the numbers were different. The Hare’s dice resembled a slugger in baseball; he is either going to bash a homerun or strike out. The Hare could roll a 6 or a 12 or 0, nothing in between. The Tortoise, on the other hand, could never roll a zero or a twelve. The value of each roll resulted in much smaller combinations, never higher than 6, but moved with every roll. The Fox was somewhere in between, the Goldilocks of the group. It was a game of odds really, whereby any of the three could, and did win, the game.

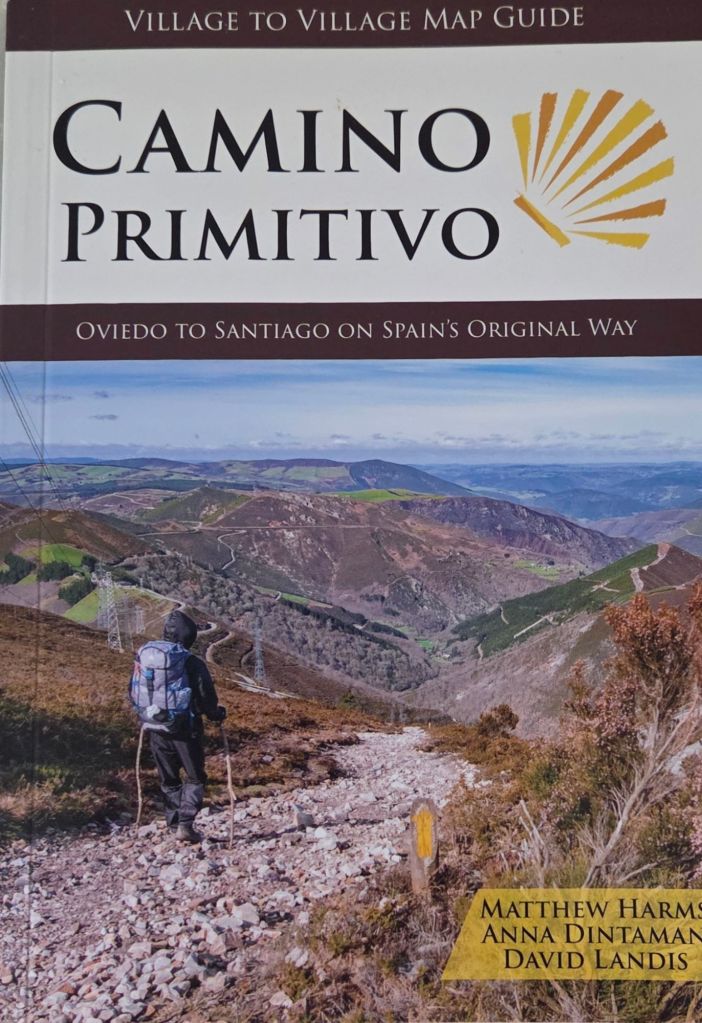

The Camino is not a race and everyone wins in participation. The peregrinos walking the Primitivo, however, reminded me of this family memory. I started recalling the people we met earlier on the Way and those who we encountered today. I kept imagining which one of the three animals they resembled and classified them accordingly.

Izzy, the young woman from Britain is a Hare. She spoke with us very early into the Grado to Salas stage and apologized before moving on; she had started late and needed to get to Salas. We never saw her again until the next morning, at our hotel, for breakfast. Olga and I were finding our seat when Izzy was doing the same. Hello, how are you, nice to see you again, then straight into her meal. She was gone before we finished. It would be our only sighting on the trail. Izzy is the type of walker who rolls double sixes regularly, the occasional six on a big hill, and only a zero at lunch time.

The Fox is represented by this German couple (never got to exchanging names) who we passed on the big climb, only her at first because he had taken a detour and would catch up. They passed us later, then we passed them on their lunch break, then they caught up again and eventually we lost sight altogether.

Without question, Olga and I represent the Tortoise; slow and steady, rolling a variety of numbers yet always moving forward.

This third stage, Salas to Tineo, begins with a long 5.7 km incline of 460m through a forest along a path of rocky terrain. The success of the previous day generated a bit of over confidence in our physical capabilities, forgoing stretches and ankle taping which had been an important element of the previous segment. Our dice rolls were a consistent 3 or 4, an occasional 2, but a generally steady climb befitting the pace of the amphibious creature.

The toll of day one, and the added length of day two caught up with us when we reached the top. The soreness in Olga’s ankle flared up, hurting to the extent we had to stop and give it attention. The tape which had been helpful the day before was now applied. Two Tylenol tablets were swallowed to address the pain. We would continue believing the shin would work itself out. The dice rolls were now a consistent 2. And there was still a long way to go.

Olga bravely hobbled along, persistent, deliberate. She needed to stop regulalry to alleviate the pain, which had the advantage of being able to gaze longer at the glorious views from our elevated vantage point. We spoke to the cows and horses from the numerous farms, and greeted each pilgrim, by bike and by foot, who passed.

One such pair, coincidentally German, Tom and Lydia, commented on Olga’s perseverance in spite of the apparent strain; slow and steady they said, take your time, you will get to Tineo. They were the epitome of a Fox pilgrim, strolling, exploring, engaging. We caught up with them at a Camino path watering stop. Tom’s command of English was better than Lydia’s. He began asking questions of concern, offering medication, providing words of encouragement. We met them again later at a small church for a few moments of contemplation. “See”, he chuckled, “your not losing any time.” We did not see them again. Their rolls were always greater than our results.

Olga suggested contacting a taxi to take her into Tineo and I could walk the remainder to meet her at the hotel. This town would have been our last possibility before the final leg. I could not figure out how to connect with a company, my e-sim does not allow phone calls; besides my Spanish and their English is nonexistent. Let’s keep moving. We have time.

The dice rolls kept coming up as 1. Stop, rest the leg, injest some sustenance, carry-on. Ever slower. By the time we reached the edge of Tineo, still 1.5 km away from our hotel, the dice could not be rolled any more. Olga could not continue. She leaned against the lamp post, head bent. Done. We were rescued by the mercy of an angel in the shape of an elderly Spanish man passing by, who, without a word of English, managed to convey the message that he would get his car to drive us the remainder of the way. We staggered into our room at the end of another long walk: 23.8 km, 33,374 steps.

I stumbled upon Izzy in the lobby. The Hare arrived at 2:00 pm, five hours faster than the Tortoise. She is going to continue again tomorrow, so sorry to hear about Olga’s shin, maybe we will meet again down the road.

I doubt it. Olga needs time to repair and recuperate. We need to adjust our plans and regroup. The climbs are only steeper and descents ever sharper in the next two stages of the Primitivo. A couple days here in Tineo will help clarify our next move.

As long as we are together, we will figure it out.

Buen Camino