We had gone around the table, asking each of my cousins from the van der Weil family for one word to describe Oom Cees. Finally coming to Margaret, she proclaimed, without hesitation, “modern ideas”.

Olga and I were in the Netherlands in part to meet with my relatives and to conduct some research into the life of Fr. Cees de Cock. The van der Weil siblings are older and in one of the best positions to remember him, everyone with a story, many with a photo or an artefact of significance. My cousins and their spouses gathered in Trus’ home, the eldest, in Tilburg, for some coffee and drinks and pastry. It is a family which loves the opportunity to get together and a visit from a Canadian cousin seemed as a good a reason as any. Most answered the describe-in-one-word question with predictable adjectives – integrity, modesty, humility. Margaret’s words did not truly resonate until last year when I was reviewing the material in preparation my visit to the Mill Hill archives and our return to the Netherlands this past spring.

In advance of our arrival, I wrote to Margaret to ask what she meant, could she elaborate. Not surprisingly she could not recall her answer eight years earlier. Thinking back, Margaret wrote she may have been attempting to express the notion, open mindedness. “He was not a missionary who started preaching strict rules of the Catholic Church. Of course he did preach the Christian faith. And he put the Christian faith into practice, literally rolled up his sleeves himself. And that appeals to people. Anywhere in the world.”

In April, the family was again gathered, this time at Margaret’s house in Waalwijk. And as per these reunions, there was plenty of stories and laughter, remembering the past. The topic of conversation inevitably led to Oom Cees. Geert addressed me directly, wanting to expound upon Margaret’s response to my inquiry. Clearly they had been talking about my question. Geert viewed Oom Cees as a missionary more concerned with work that contributed to the lives of the people, supporting them with the development of buildings and schools and hospitals rather than focusing on saving their souls. The explanation was aligned with my own understanding.

Recently, I was reviewing material from my week in the archives. The discoveries included reports on the conditions of Uganda for the clergy and the people. I did not read them in detail at the time, instead electronically scanning them for future reference to help place the life of my uncle in context. One such report for the Diocese of Tororo in 1956 by the Society Superior, spent several paragraphs briefing the Superior General on “Spirituality”. In his opinion, many of the Fathers were lacking in the spirit of piety, not deriving inspiration from spiritual exercises such as community prayers, meditation, or mass; rather, they gave preference to external activities, not properly priestly, such as building. As one piece of evidence, the Society Superior observed priests, both old and young, “rarely entering the church for a short visit to Our Lord despite passing the church several times in the course of the day’s work”.

“To put it rather bluntly, some prefer bricks to souls, finding perhaps the former more pliable than the latter.”

Uncle Cees would likely have been considered amongst the young at the time of this report. Freshly ordained, Fr. Cees de Cock arrived in 1947 at the age of 25, and similar to other new priests, he moved around among the various parishes as a temporary curate, replacing those on scheduled or medical leaves. Whether he would have been amongst the ones who preferred “bricks to souls” may not have been evident to the Society Superior. Uncle Cees was on home leave in that year and given his “spare part” assignments, may only have been involved in the ongoing projects started by the residing pastor.

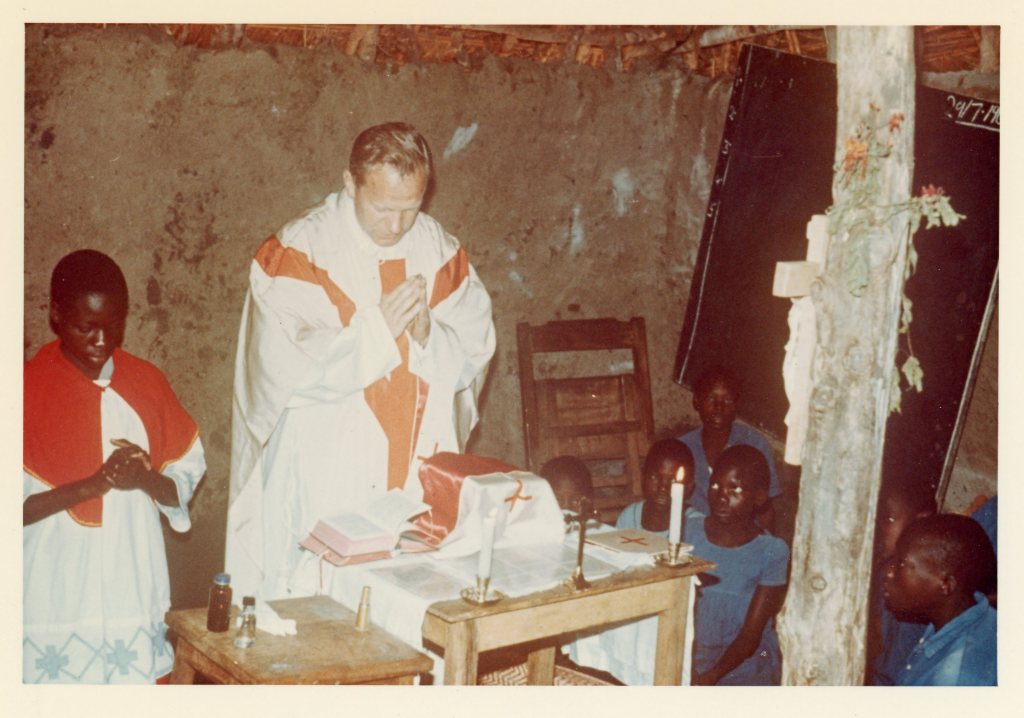

In 1957, Fr. Cees de Cock became the pastor for Kamuli Parish where he remained until his untimely death January 2, 1981. Uncle Cees was responsible for a long list of accomplishments in those 33 years many of which were provided to me with much enthusiasm and pride during my very brief visit in 2017. The “Late Rev. Fr. C. De Cock’s Profile in Kamuli Catholic Parish” described him as possessing “many practical skills”, including, Engineer/Mechanic, Builder, Plumber and Hunter. He was responsible for the Lubaga Boys Primary School, St. Pius X Junior School, St. Francis block in Kamuli Mission Hospital, the water pipes/system for Kamuli Mission Hospital, the Headmaster home for St. John Bosco Secondary School, and the De Cock Memorial Hall so named in his memory. His talents were utilized to establish churches at Nawanyago, Matuumu, Kidiki, Balawoli, and Bugulumbya. During my visit, Stephen Dhizaala and Fr. Wijnand Huis guided me on a tour to a handful of examples of the local development.

Simultaneously, Fr. Cees de Cock was revered as a priest and a person, one who was an integral member of the community, a spiritual leader remembered for his generosity, his humour, his quiet demeanor, his dedication to the people. Mention of his priestly obligations were numerous although his willingness to work with them, his effort to be one of them, his respect for them comprised the sentiments they wanted to impress upon me on that auspicious day.

Uncle Cees appeared to be a priest in mind and practice consistent with the words of Herman Hofte, a classmate and fellow missionary in Uganda. In his depiction of the work, Fr. Hofte attended to the priestly functions – mass, confessions, baptisms – but thought missionary work was mostly about Christians living as an example, as part of a “welcoming church” for those who became interested. Fr. Hofte spoke about people working behind desks, who invented the rules, whereas he found the practice of daily life much more important.

In my estimation, the Society Superior misread the activities of the missionaries he observed. Rather than preferring bricks to souls, they won over souls in tending to the bricks.

An academic interpretation of missionary work would suggest that the act of building was a tactic for the long-term strategy of conversion to Catholicism. Indeed, the intent of the church in Uganda would follow this logic. And it would be naive to believe this goal wasn’t their aim.

My reading of the individual priests and brothers, however, suggests the experience of living amongst the Ugandan people converted many of the missionaries, a transformation of their own souls to a personal destiny to support the needs of the communities they served. The schools and the hospitals were built for the community regardless of religion. The inadequate infrastructure was not being addressed by the government or any other social agency, so the missionaries stepped up and were able to contribute. Yes, the churches they built were Catholic although I can speculate with confidence that credentials were not checked at the door.

Uncle Cees happened to be in the Netherlands when Idi Amin staged the military coup to attain power. The gravity of the situation would have handed him an easy excuse to delay or cancel any return to what would become several years of terror. Instead, he made arrangements immediately to fly to Uganda, to the diocese, to the people. Francis Isabirye related this story during my visit as evidence for Uncle Cees’ love for the people. From the outside, Francis emphasized, he could be conceived as a mad man or a very foolish man; yet, he defied conventional logic so he could be with his people.

In an earlier letter exchange with Cees van Deursen, I had asked what he recalled as my Uncle’s approach to Catholic theology. Dr. van Deursen couldn’t answer directly except to compare Fr. de Cock’s approach to his own uncle, a Benedictine monk who preferred working to praying, adapting St. Benedictine’s adage, “ora et labora” (pray and work) to ‘my working is praying”. My Uncle, according to Cees, operated in the same manner.

I am reminded of the words written by Bishop Willigers in memory of Fr. Cees de Cock, a tribute which continues to shepherd me in this journey of discovery: “Those from Kamuli recognized in Cees what a true priest really is according to the model of our Lord.”

Margaret remembered Oom Cees as a serious student of the faith with a deep understanding of the Bible. She recalled a story whereby Oom Cees greeted a Jehovah Witness couple at the door where he was residing while in the Netherlands. The pair cited passages from the Bible, largely Old Testament, which portrayed a foreboding of doom and the need for salvation to which Oom Cees listened and responded with other quotes on the same subject that contained a positive message of hope. “In any case, he was an intelligent, wise priest. It was always very nice and easy to listen to him, for everyone. He also was an ordinary and modest man; close to the people and I think open minded in his time. Maybe that is why I called him “modern”?”

Uncle Cees helped build a community with bricks and shaped the people’s souls. The buildings may crumble but his soul will be remembered.

Even so faith, if it hath not works, is dead, being alone. Yea, a man may say, Thou hast faith, and I have works: shew me thy faith without thy works, and I will shew thee my faith by my works. James 2: 17-18. King James version.

Very very nice. Thanks for sharing.

Get Outlook for iOShttps://aka.ms/o0ukef

LikeLike

Having lived in Africa all my life and now in a part of it where missionaries were very active, your statement, Rather than preferring bricks to souls, they won over souls in tending to the bricks resonates with me. I think it might have been difficult for people living in Europe to judge the need for both physical and spiritual upliftment in areas where people had so little. The dedication of some missionaries to learn the local language, to inspire the development of the communities they worked with and assisting people to make the best of what they had. I suspect Cees was one of these.

LikeLike

Thank you for your insight. Sometimes I find it difficult to speak or write about missionary work given the sordid history here and portrayed in other parts of the world. There is a tendency to think in general, blanket terms rather than the individual.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A wonderfull description of how much Uncle Kees loved “his people” with heart and soul!!

LikeLiked by 1 person